Salida de un socio del accionariado

Salida de un socio del accionariado

Tax implications of the exit of a shareholder from the shareholder structure

In family businesses, it is common to find certain corporate conflicts that can be resolved with the exit of the dissatisfied partner (or partners). In this article, we will explain the tax implications of the exit of a partner from the shareholding of a business entity.

This issue is covered by the Capital Companies Act (LSC). Specifically, Title IX of this legal text regulates the so-called ‘Separation of Shareholders’ (articles 346 to 359 of this legal text). This figure allows the shareholder to separate from an entity provided that there are a series of specified causes (non-distribution of dividends, modification of the corporate purpose, etc.).

There are various ways to carry out this exit. One of the most common is the sale of the shares or holdings to the company itself, which, once acquired as treasury stock, will carry out a capital reduction to amortise them.

That said, it should be borne in mind that this type of transaction has a number of tax implications that should be taken into account when planning and executing them.

What are the tax implications of the exit of a shareholder from the shareholding of a commercial entity?

In order to develop the taxation of this type of transaction, a distinction must be made between the partnership and the separating partner.

Implications for the company of the exit of a shareholder from the partnership

In the case of the company that has repaid the shares or holdings to the exiting shareholder, the tax effects will depend on the nature of what the company has given to the shareholder who has decided to leave the project.

If the company pays this amount in cash, it will not generate any accounting profit and therefore will not be taxed on this transaction.

On the other hand, if the company hands over other types of assets it owns to the exiting partner (real estate, machinery, financial investments, etc.), an income may arise from the difference between the market value of the assets handed over and their tax value.

In the event that the market value is higher than the tax value, this delivery will result in a profit for the company, which would generally be taxed at 25%.

Implications for the exiting shareholder of the shareholding of a business entity

Regarding the shareholder who leaves the company, in order to be able to distinguish between a shareholder who is a legal entity and a shareholder who is a natural person, a distinction must be made between them.

For these purposes, it should be noted that this possible positive income may be 95% tax exempt if the requirements are met to be able to apply the exemption provided for in article 21 of Law 27/2014, of 27 November, on Corporate Tax (LIS hereinafter).

Without wishing to be exhaustive, the requirements of this provision to apply this 95% exemption are as follows:

- The shareholder’s shareholding in the company must be at least 5%.

- That this participation has been maintained for at least one year prior to this separation.

- It is not representative of a company that has the status of an asset-holding company.

Furthermore, as an unavoidable condition of this exemption, if the partner’s exit results in negative income and the aforementioned requirements are met, this income cannot be included in the taxable income for tax purposes.

Secondly, if the partner is a natural person, this transfer would be subject to Personal Income Tax (IRPF)[1].

Traditionally, this issue has been very controversial, as the tax authorities classified this positive income as income from movable capital and therefore denied the application of the abatement coefficients.

Only in the event that this separation took place for one of the reasons indicated in the commercial regulations did the tax authorities allow the income to be classified as a capital gain and permit the application of these coefficients.

Currently, we understand that this controversy has been resolved thanks to the Resolution of the Central Economic-Administrative Court (TEAC) of 11 September 2017, which confirmed that this income should be classified as capital gains in all cases and, therefore, these coefficients may be applied provided that they fall within their scope of application.

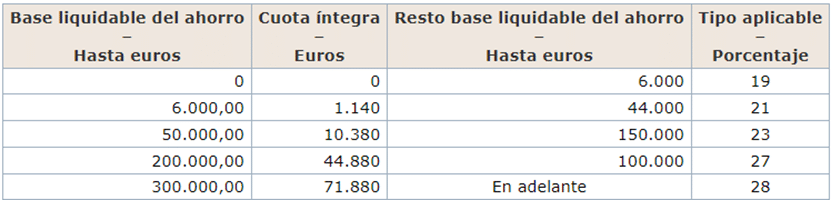

That said, regardless of its application, this income will be taxed in the individual’s savings tax base, the current tax rates for which are shown in the table below:

Tax implications of the exit of a shareholder from the shareholding of a commercial entity in indirect taxation

As the casuistry in this section can be very high, we simply wish to point out that this type of operation may be subject to Value Added Tax (VAT) when the refund made to the shareholder is non-monetary. However, it should also be kept in mind that some of the exemptions provided for in these regulations may be applicable.

In addition, if the transaction is instrumented as a capital reduction with return of contributions, it should be noted that it will be taxed under Corporate Operations (OS) of the Transfer Tax and Stamp Duty (ITP and AJD) at 1% of the value delivered to the exiting shareholder.

Would it be possible to deal with the departure of a partner by means of a corporate transaction to which the special tax deferral regime applies?

Usually, in order to reduce the tax costs associated with an exit of partners, corporate restructuring operations are envisaged.

One of the most frequently carried out operations and, consequently, one of the most frequently reviewed by the Tax Inspectorate is the full demerger.

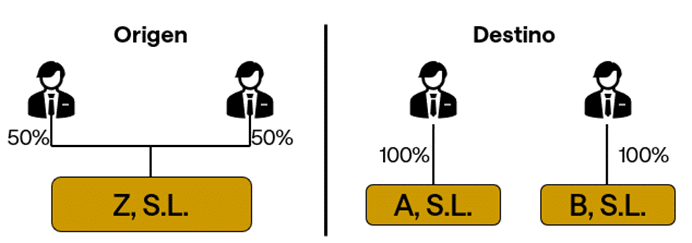

Specifically, we are referring to a full demerger operation in which the company’s assets are divided between the partners and each partner retains a share of equal value.

Graphically, the operation we are describing could be represented as follows:

As can be seen, this operation has allowed the assets of Z, S.L. to be separated through the creation of A, S.L. and B, S.L. and, in addition, each partner will hold 100% of the capital of both companies.

Although this operation is totally viable from a commercial point of view, it should be considered that the General Directorate for Taxation (DGT) has been demanding in this type of operation that, in addition to respecting the quantitative proportion (value of what is received by the shareholders), the qualitative proportion must also be respected (the shareholders of the spun-off company must be shareholders of the entities benefiting from the spin-off).

For this reason, in order for the full demerger set out in the chart above to be viable for DGT, the partners must each have a 50/50 shareholding in A, S.L. and B, S.L.

Only in cases where the split assets arising from the division of Z, S.L. constitute branches of activity for corporate income tax purposes is it possible for the allocation to the shareholders to be qualitatively non-proportional.

This opinion has been endorsed both by the TEAC (Resolution 2162/2015 of 18 September 2018) and by various rulings of the National High Court (among others, its ruling of 28 November 2018).

However, two recent developments have to be taken into account:

- First, the High Court of Justice of Castilla y León (TSJCL) has indicated that the requirement of branches of activity in the case of a non-proportional spin-off does not comply with Directive 2009/133/EC (Merger Directive) and, therefore, the application of this special tax regime cannot be rejected due to the lack of qualitative proportionality.

- Secondly, the Supreme Court has accepted an appeal in cassation on this issue. Among other questions, the high court must determine whether, in the case of total and non-proportional divisions of companies, it is in accordance with EU law to make the application of the tax neutrality regime conditional on the acquired assets constituting distinct branches of activity.

With regard to the latter order, it should be highlighted that the Supreme Court ruled on the matter in its judgment of 20 July 2014 and concluded that no contravention of state legislation with European Union law could be detected.

However, although the ruling of the TSJCL is very favourable to taxpayers, it should not be forgotten that it is an isolated ruling and, at the time of writing, we are not aware that the Supreme Court has responded to the appeal.

For this reason, in order to avoid undesirable surprises in this type of operations, it is highly recommended that taxpayers have specific tax advice.

Do you need advice? Access our areas related to the exit of a shareholder and family business:

[1] Before going into its analysis, we would like to point out that we are going to refrain from analysing how the calculation of the possible capital gain that the individual partner may have would be carried out, as this would detract from the purpose of this post. Moreover, this question will be dealt with in subsequent publications.